Welcome to Week 5 of my Carrying Independence serialization! Each Wednesday, I'll share another chapter as we count down to America's 250th birthday.

Today in Chapter 5, Nathaniel, Arthur, and Kalawi return to the Shawnee clan—reporting on what they’ve learned—as the three friends grapple with the reality that war has truly arrived. (Chapter one began here.)

Chapter 5

NAKOMTHA WAS WAITING. Kalawi's mother was steadfastly surveying the thicket of white oaks through which they came, her slight figure as stately as a statue carved at the edge of the village. The afternoon sun alighted the handful of gray just beginning to show at her crown as she shielded her eyes with a strong hand. As always, Nathaniel felt a sense of calm settle deep into his bones at seeing her, and returning to the village.

The land east of Nathaniel's farm was an abundant haven for the Shawnee clan. The Wolf Clan came each spring when the star magnolias bloomed, rebuilding the circle of nearly thirty wegiwa, longhouses covered in bark and skins, facing a central council house. They would reclaim the fallow field that ran between the corn and creek to use for their dances and games. The clansmen would hunt alongside Nathaniel and Arthur until after the Green Corn Celebration—when the gold of fall had blown from the trees, and the harvest complete—moving to higher grounds in the mountains. Nathaniel would wait through long, silent winters for their laughter to return along with the trilling chatter of the first yellow warblers.

Now, as the three boys rode into camp, a small group of older men playing handball in the gaming field ran to greet them. The children flew like geese from Saucony Creek to gather around the skirts of the women who abandoned their beadwork and tanning. The fifty or so welcoming smiles of the clan quickly fell at the sight of the men returning without quarry.

"M'sikkanwi—the wind—it has shifted," Kalawi said, as they dismounted.

"Lamatahpee." Nakomtha told the clan members to sit, waving a hand toward a fire pit outside the council house, a crease deepening in her otherwise smooth brow. She helped to settle Wapishi, the clan's eldest male, in the innermost circle. The shock of white hair he'd had since birth gave him the name, and though he was once a robust warrior, he now folded himself onto bony limbs.

With Arthur and Nathaniel seated close by, Kalawi took his rightful place next to his mother. As he relayed the morning's events, murmurs of worry and sadness rose and fell. Kalawi ended with Anderson's final warning, then looked to his mother for guidance.

They called her Nakomtha, or grandmother, after the Great Spirit, Waashaa Monetoo. Shortly after Kalawi was born, her husband and nearly two dozen of the elder clansmen had been killed in a battle against the Cherokee—a battle which she as their Civil Chief, or hokima, advised them to not fight. With their numbers severely reduced, the clan had migrated north to Berks County to join another small faction of the Wolf Clan. Over the years, Wapishi had pressed his tongue into the space where his front teeth used to be, encouraging Nakomtha to speak for the clan.

"This Mr. Anderson," Nakomtha said, her voice pensive, "this man who spoke of the English family's quarrel…"

Kalawi opened his mouth to speak, but Nakomtha placed a hand gently on his knee.

"I know you want to share what you think. It is more important to tell us what you did not hear."

Nathaniel waited with the clan. Kalawi would turn eighteen in October. As the son of Nakomtha and the clan's past chief, he would soon be expected to assume leadership. Though he had to publicly suffer these teaching moments, Kalawi's inheritance also came with an enviable benefit. He was free to choose a wife this year, and she would become the new hokima, her voice nearly equal to his own. Nathaniel had encouraged Kalawi to choose wisely, and now he waited with the whole of the clan to learn what concerned his friend most.

"He did call us barbarians, but…" Kalawi blinked several times, clearly working hard to be the man they needed him to be, "he did not call us peacekeepers, despite our Mekocke division striving to keep peaceful relations with English settlers."

Nathaniel had long ago learned the Shawnee were governed by five divisions. The Kispokotha counseled on matters of war. The Thawegila and Chalagawtha were leaders in times of peace, and the Pekowitha were the helpers. The Mekocke division—to which Kalawi's Wolf Clan belonged—governed medicine, and had been among those who had negotiated treaties, even in nearby Philadelphia.

"Perhaps Mr. Anderson sees what I saw a year ago in Chillicothe." Nakomtha turned her oval face south, her dark eyes searching the light as if retracing her journey to the tribe's annual meeting grounds of division delegates. "The Shawnee were splitting into two factions. Some of the Chalagawtha and Pekowitha members were involved in raiding white settlements in western Pennsylvania, Kentucky, and Virginia."

"Are these factions aligned behind different leaders?" Kalawi asked

"A-ha, niiswi." Yes, two. Nakomtha smiled, clearly pleased with his question. "Hokoleswka from the Ohio—the whites call him Cornstalk—urges conciliation. But Blue Jacket of the South… Two years ago, he clashed against the British Governor Dunmore in Virginia, but then at Chillicothe he suggested we align with the British. He has an unpredictable heat."

Kalawi contemplated Nakomtha's words, then swept an arm toward the clan's cornfields, stalks shoulder-high, and just beginning to turn green. "Anderson also said nothing about the land they will fight upon."

"Fight for," Nathaniel spoke, knowing he was free to contribute. "My father says British and colonists both want ownership of American lands. On the Ohio and in Kentucky. Even here along Saucony Creek."

Although most Shawnee had migrated further west into the Ohio Valley in the 1760s, the land upon Saucony Creek had stayed a protected refuge for the Wolf Clan. For how much longer, Nathaniel now wondered. "Both sides believe the land has a price."

Kalawi sniffed. "That we believe the land is free to everyone is what frightens them most."

"Mata." No. Arthur held up a single finger. "It is that you believe one man cannot rule another. Between tribes and within your people. If a few Shawnee are on the war path, they assume all Indian nations run wild together."

"White men and our people…" Wapishi let out a low moan, dusty with age. "We suffer the same ignorant opinion of one another; we are each barbarians."

"And your land?" Nakomtha turned to Arthur and Nathaniel. "Do you consider it British or American?"

"The soil is British Pennsylvania—land granted to our grandfathers. But our estate is also our rifling business." Nathaniel was certain even Peter would agree. "Though, even that is changing." He told them of Peter's command to increase production for the militia.

"And this spring, as Congress requested, we waited to slaughter our sheep until after May," Arthur added, "to shear more wool for uniforms and blankets for the Continental Army."

"Your flocks graze upon British grasses, and grow wool for Continental soldiers?" Nakomtha raised an eyebrow.

Wapishi clicked his tongue. "So even the sheep are uncertain who to follow."

Arthur picked at the grass at his feet. "Some of us are not so uncertain."

"One of us, you mean," Kalawi said.

"My family once fought for Great Britain." Arthur squared his shoulders. "Now the King sends his Royal troops to kill their American grandsons. Shouldn't which nation to fight for be obvious?"

"Maybe to you who were never British." Nathaniel bristled. "Which nation would I fight for exactly, Arthur?"

"Yes, which nation?" Kalawi's dark glare snapped between them.

Breaking through the heat in the circle, came Nakomtha's low chuckle.

"How is this funny, Mother?" Kalawi turned his gaze on her.

"I knew this day would come. Three boys from three families." She pointed to each of them, the smile unwavering. "You began life swaddled in three different blankets, until Topton Mountain stitched them together."

"How did a mountain do that?" A young Shawnee girl nearest Nakomtha asked.

"You've not yet heard the tale of their meeting?" Nakomtha asked.

The little girl shook her head, her short braids swinging. "It is Kalawi's favorite story! It would serve you well to recall it now."

Kalawi crossed his arms and looked away, but Nakomtha took a long breath. "Very well, I will start it for you. Autumn's Corn Goddess had already painted the leaves on Topton Mountain when eight-year-old Kalawi ventured into the forest. Alone."

When the little girl gasped, eyes wide, and before Nakomtha could encourage him again, Kalawi took up where she left off. He couldn't help himself.

"I was seven, the time of each Shawnee's Vision Quest. I left the village as the sun came up, to search for my spirit. My purpose." He tapped his own chest with a fist, and the clan's few teenage girls giggled. "Day turned to night. Night to day. As the moon climbed high the second night, I began to grow weary. Was I to find the spirit or was she to find me? In the darkness I found a large flat rock in a clearing. I climbed upon it and I waited for her silently—"

"A difficult task for our young Kalawi," Arthur said. A ripple of laughter moved through the clan but Kalawi waved away Arthur's comment.

"I did stay silent. But then I heard a song pulled from me, calling out to my spirit, bringing her toward me. With her came the mist. It swirled through the trees and enveloped the mountain, swept into the clearing, and my spirit settled on the ground before me."

"You saw her?" The littlest girl's eyes were wide.

"Yes, but I was not the only one." At last, Kalawi smiled at Arthur and Nathaniel.

"Arthur and I were lost in the haze." Nathaniel felt his chest warm with the memory. "We'd passed the same hollow tree three times before coming into the clearing. That's when we saw her."

"M'wah!" Kalawi breathed. A wolf. When the little girl covered her mouth, Kalawi leaned toward her. "Black eyes set deep in snowy white fur. More than twice my size, yet she was gentle, like a soft wind."

"Mysterious as the fog," Nathaniel said, lost in the memory.

"Like the moon." Arthur stared up at the sky, though the late afternoon sun still shone.

"Like the moon," Kalawi nodded. "But then the wolf swiftly stood. I feared she might come toward me, but instead she looked back over her shoulder, to the edge of the clearing. There were Arthur and Nathaniel. When the wolf padded away, she took the fog with her, and left the moon shining down upon the three of us."

"It was not long after, we created the brave knight's oath," Arthur said.

One at a time, taking turns, line by line, the three recited it.

Push with prowess through the world

Not by another's will, but for a nobler goal

Protect the meek

Secure a fair maiden

Honor the past with humility

Step gently into the future

And so on this journey we each our own way go…

Wela ket nee ko ge.

"We are one." Nathaniel translated the last line.

"Wela ket nee ko ge. The wolf, she had called together your spirits." Nakomtha smiled warmly at the three friends, and her melodic voice softened further as she turned to the little girl. "Arthur and Nathaniel were welcomed into our Wolf Clan. So now they help carry our messawmi, a sacred message for the Shawnee tribe. All of us carry it, as one, but each Shawnee also has a pawaka: a sacred bundle, deep in their hearts, to guide themselves."

Nakomtha interlaced her own fingers and showed the girl her hands. "The messawmi and everyone's pawaka are woven together, inseparable. The question we each must answer is how our sacred bundle will become part of the tribe's fabric. Your pawaka, your sacred bundle, will present itself to you when you are ready to carry it." She looked to each of the three boys separately, her gaze landing last, and fully, upon Nathaniel. Her next words made his heart pound. "You must be prepared to receive it, to choose how you will contribute. If you do not choose, a choice will always be made for you."

Nathaniel looked to his two friends, their attentions cast inward as they each contemplated her words. Nathaniel wondered how their three different views could possibly unite in a single vision for the tribe. How could he, an ordinary second son of a gunsmith, do anything of significance for a whole people?

"Nathaniel!"

The shout came from the edge of the town, startling the pensive clan. They all turned in unison toward the thicket not two dozen yards away, where Peter sat stiffly astride a grey mare, both hands clasping the reins.

"Mother calls you home for dinner. And we have work to do." Peter's dark eyes briefly fell on Nathaniel's horse, devoid of elk, before turning into the woods for home. Nathaniel's face grew hot, and he scowled at his brother's retreating back. As the clan members rose from the circle and began to disperse, Nakomtha came to Nathaniel, and put a hand on his arm.

"Leaves upon the same tree do not all receive the same amount of sunshine; those that thrive in the damp shadows and those that reach for the light are both required for the tree to survive."

Nathaniel nodded, but Peter's presence reminded him of the journey ahead. He told Nakomtha of their trip to Philadelphia, adding, "Perhaps we can discover what this separation might mean for the tribe."

"We will learn more at my Uncle Bowman's." Arthur dusted off his breeches, and fetched their horses.

Once again Nathaniel's thoughts flew to the colonel's home. To Susannah. Nathaniel saw her curtsying as she had after their first dance—her golden hair framing her face, peering up at him through lowered lashes.

"You both usually return from a visit with this cousin of yours far more civilized." Kalawi winked at Nathaniel as he embraced Arthur goodbye, giving his friend's armpit a good sniff. "Less like those elk."

Arthur punched him as Kalawi turned to Nathaniel, holding him at arm's length. "Go, knowing I go with you. We are one, my brothers."

"Wela ket nee ko ge," Nathaniel replied as they embraced.

They mounted their horses, and Arthur led them from the Shawnee town. He rode off, bouncing and waving his hat over his head, his thoughts already turned toward the luxury of his uncle's refined house, a fair change from his rural home bursting with the noise of all his siblings.

Nathaniel, slower to follow, kept his eye upon Nakomtha and Kalawi until he reached the thicket. He drew in a deep breath to hold onto them, missing their counsel and friendship already. When the trees closed behind him, he turned forward in his saddle. He braced himself for the task that would await him when he arrived home. He knew he had to do what Peter would not. He had to say the four words that would make his mother cry.

Join us next week as Nathaniel returns to his Berks County farm. As talk turns to politics before he leaves for Philadelphia, his worries over the fate of his family deepen.

Join the Conversation

Childhood is a simpler time, but as we age—and the real world shuffles in—we are often faced with opposing choices. Do you choose what is right for yourself (your pawaka) or for all those around you (mesawmi)? Or both? Are they always those choices intertwined?

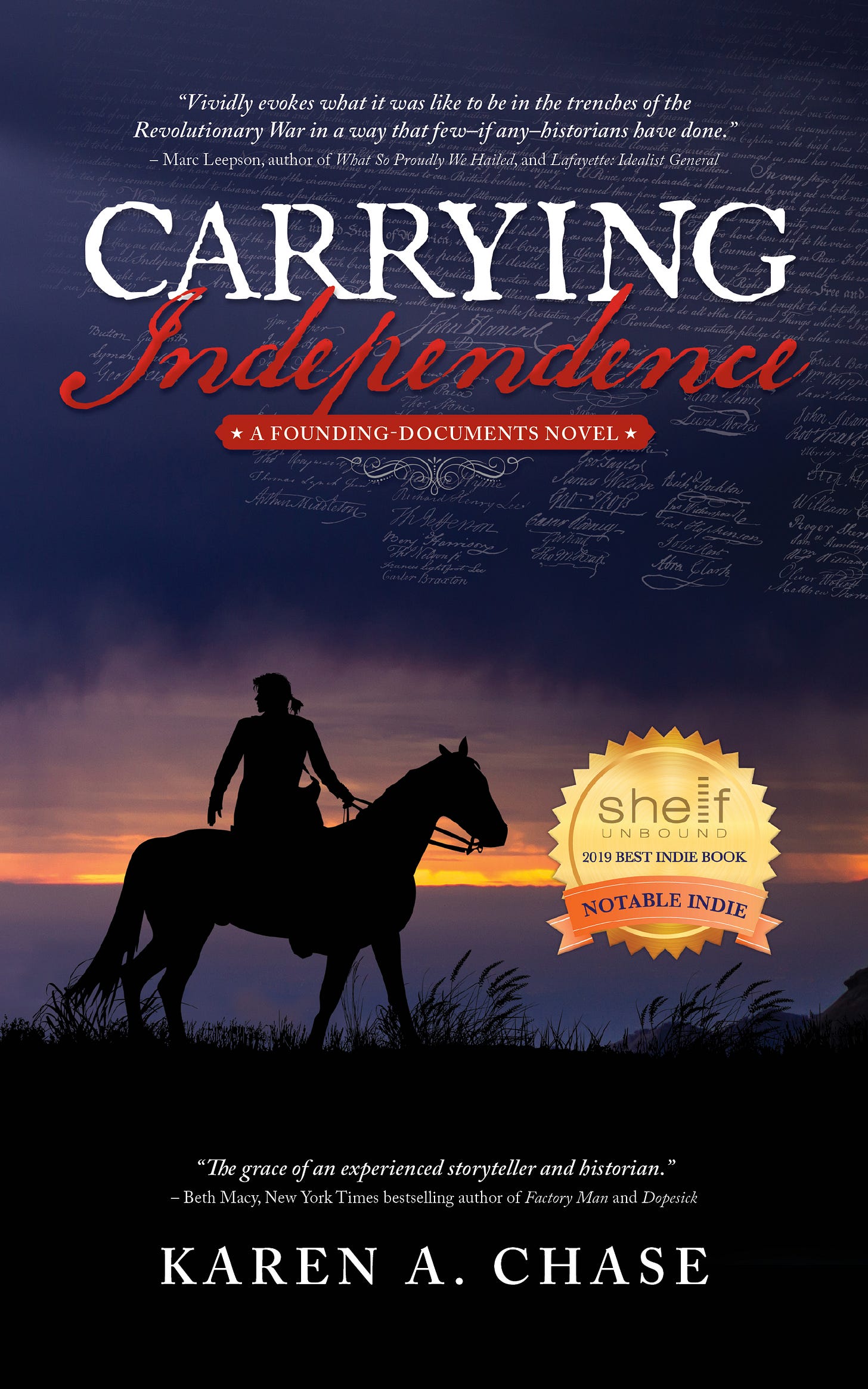

This chapter is part of "Carrying Independence," a historical novel following the journey of the Declaration of Independence as Nathaniel, a reluctant Post rider, gathered the signatures needed to unite America. If you're enjoying Nathaniel's story and don't want to wait for the next installment, autographed copies of the complete novel are available here.

The Shawnee community in the colonies, when we declared independence, was a group divided. Not for British versus American as so many of our teachings still convey. Instead, a significant portion of the Shawnee who followed Hokoleskwa (Cornstalk), wanted to support a traditional nation. Their own!

Unlike those who followed the warring leader, Blue Jacket, peaceful sects and clans wanted above all else to remain Shawnee. Colin Calloway, a National Book Award recipient, recounts their struggles in his works like, "The Shawnees and the War for America." His review of my novel along with current Shawnee tribal members, like Sherman Tiger, helped me show the Shawnee more thoughtfully—as seeking independence, too. This Chapter 5 of my FREE Substack serialization of my RevWar novel shows this more nuanced viewpoint.